Transcript

Jack Shaheen

Strategies to Successfully Push Back Against Harmful

Hollywood Stereotypes About Arabs and Muslims, and the Work New

Generations Must Take On

Dale

Sprusansky:

Our next speaker, many of you

know, truly needs no introduction.

Jack Shaheen is an internationally acclaimed author and media

critic. His lectures and

writing include many, many things.

His books include A

Is for Arab: Archiving Stereotypes in U.S. Popular Culture,

and Guilty: Hollywood’s

Verdict on Arabs After 9/11.

He’s been in this field for an incredibly long amount of

time, and we couldn’t be happier to have him here today.

His book signing will be at 6:00, rescheduled from lunchtime.

Ladies and gentlemen, Jack Shaheen.

Jack

Shaheen:

Well, colleagues, guest speakers, friends—heartfelt thanks

for your participation today.

It’s extremely, it’s wonderful to be here.

My heart belongs with the

Washington Report, mainly because the first speech I ever

gave on stereotyping was in Beirut, and the man who sat in the front

row was the Delinda Hanley’s father, Richard Curtiss. [APPLAUSE]

Anyway, to paraphrase Plato, those who tell the stories rule

society. Flashback 1962,

President John Fitzgerald Kennedy, commencement address at Yale

University: “Damaging myths are doing our nation a great disservice.

The great enemy of truth is very often not the lie,

deliberate, contrived and dishonest, but the myth, the

myth—persistent, persuasive, and realistic.”

Now journey with me briefly this afternoon as I offer five

suggestions as to how to contest those persistent myths about Arabs

and Muslims. First, a

bit of history: for nearly half a century—I know I look much younger

than I am—I’ve tracked Hollywood’s Arabs and Muslims.

Almost always, I found they appear as villains.

They’re godless, evil, enemy, other.

Renewed and repeated over and over again, these images are

hardwired into our psyches.

As the Arab proverb reminds us, “By repetition even the

donkey learns.”

Islamophobia has joined Arabophobia.

Prejudices are escalating, not diminishing.

Today’s villains are not just Arabs and Muslims from over

there. They are

homegrown Americans with Arab roots, and American Muslims, including

Muslims from countries like Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran.

Before 9/11, dark-complexioned actors portrayed Arabs from

over there as villains.

They were listed in the credits—I think this is interesting—the

credits always stated:

Terrorist #1, Terrorist #2, Terrorist #3.

They had no identity.

No names. But

today, thanks to the rise of Islamophobia, they are listed:

Jihadist #1,

Jihadist #2,

Jihadist #3.

Now in my modest opinion, the dramatic changes in villains took

place right after 9/11, due primarily to one producer by the name of

Howard Gordon, who produced the series “24.”

This Fox television series aired about 10 weeks after the

attacks. Until that

time, American Arabs and American Muslims were invisible on TV

screens. We did not

exist in media land, except for Danny Thomas in the ’60s, you know,

with the “Danny Thomas Show,” and Jamie Farr, lovable Jamie running

around in the woman’s dress in “M*A*S*H.”

That was it.

Otherwise, we just were invisible.

And then suddenly, Howard Gordon started showing Americans with Arab

roots and American Muslims as homegrown terrorists out to destroy

their country. “24” was

so successful that numerous copycat series copied that format from

“24.” Shows that I hope

none of you have ever seen, like “Threat Matrix,” “Sue Thomas:

F.B.Eye,” “The Agency,” “The Unit,” and others.

And what’s really hurtful about all of this is that Arab Americans

and Muslim Americans, like others at the World Trade Center—they

were victims. More than

three dozen were killed.

There’s never been a story about the brave Yemeni who worked in the

Marriott Hotel who lost his life saving people.

Yet here we are as victims of 9/11, and Gordon comes around

and these other image makers, and they make us the terrorists.

Today, more than ever, these villains prowl TV screens.

Arab and Muslim, along with American Arabs and Muslims, are

terrorists. They commit

heinous acts like holding students hostage in a Hawaiian high

school. They blow up

students in a coffee shop in Illinois.

They appear in popular series that I hope you don’t watch,

such as “Tyrant,” “24: Legacy,” “Madam Secretary,” “Hawaii Five-0,”

“Chicago Justice,” “Six,” “NCIS: Los Angeles,” and a score of

others.

And the shows do not project our country’s mosques as they are—holy

places of worship.

Rather, they are projected as a haven for terrorists.

God. We don’t

project synagogues or churches this way.

Why do we focus on mosques?

As Ed Murrow reminds us, “What we do not see is often as

important, if not more important, than what we do see, the sins of

omission and commission.”

Now, how to eliminate these stereotypes?

I’m not like the genie from Aladdin’s lamp, but I do have

five suggestions. The

most important is this one:

Americans with Arab roots and American Muslims, people like

writer/director Cherien Dabis, who made the movie “Amreeka” and

other films; as well as those involved in the TV series “Mr. Robot,”

Emmy Award-winners Sam Esmail and Rami Malek. Well, they’ve got to

get their act together and form a coalition of activists.

Some organizations have reached out to the industry, but no

one is more qualified, no one knows more about how best to offer

correctives, than young Arab and Muslim American image makers.

They are part of the profession.

They are on the ground in Los Angeles and in New York.

This group of activists could meet regularly with the

industry’s image makers.

Early on, as soon as they learn that a new TV show or film will be

produced.

Before the show

begins production, because once they go into production, it’s too

late.

For example, this summer there’s a new movie coming out called

“Aladdin.” It’s going to

be a live-action Disney movie directed by Guy Ritchie.

Now, not one organization—except the ADC—not one

individual—except yours truly, there may be others—has reached out

to contact Disney and Ritchie about “Aladdin.”

Why? So we could

offer constructive suggestions about how best to avoid stereotypes

that appeared in that animated version of “Aladdin.”

You know: “I come from a land from far, far away / a place

where the caravan camels roam / where they cut off your ear, if they

don’t like your face / It’s barbaric but, hey, it’s home.”

It’s important that we work with Ritchie now, to help him make a

film that will be successful, that makes a profit and that

entertains, and that Americans can go to if they have Arab roots or

American Muslims, and not be ashamed of their heritage or fear that

their children are going to be damaged by these stereotypes.

Why not? Why can’t these

image makers get together and try to lobby to make a difference?

For too many years, Arab and American Muslims have been

relegated to playing terrorists.

Fortunately, there are some who have spoken out.

My friend, Maz Jobrani, an Iranian American, told his agent,

“No more terrorists. I

don’t need to play these parts—you feel like you are selling out.”

My other friend, comedian—my friends are all comedians.

You know, I tried.

I said, I’m available, but they didn’t want anyone with grey

hair. Anyway, Ahmed

Ahmed had this to say.

He refused to change his name.

He said, quote, “I’m never going to change my name.

It’s my birth name, my given name.”

Now consider the plight of this young actor from England.

His name is Amrou Al-Kadhi.

He is a 12 year old.

When he was 12, he was cast as the son of a terrorist in

Steven Spielberg’s movie “Munich.”

“I am 26 now,” he said recently.

“I have already been sent 30 scripts for which I’ve been

asked to play terrorists on screen.”

My proposed coalition could hopefully end such typecasting.

Second, when I first started to explore this issue back in the

mid-’70s, I was alone.

With the exception of my wife and the cellphone that’s currently

ringing, there was no one around.

My wife, God love her, Bernice, stood by me, but I was the

only one. Nothing was

written. Nobody talked

about this image. Nobody

wanted to publish anything.

But now, thank goodness there are graduate students and

faculty members who write and teach about shows that humanize and

vilify Arabs and Muslims.

Now these scholars need to expand their research efforts.

How? By going

outside the walls of academe, going to Los Angeles, going to New

York, meeting with producers and writers on a one-to-one basis, as I

did in my early book, The

TV Arab. We’ve

got to make our presence known.

It’s a great way to get something published.

So that’s my advice to my colleagues in academe.

Third, more presence is needed in the media, just as more presence

is needed in politics, right?

We need more than Keith Ellison in Washington.

Anyway, presence propagates power.

“The more power you have,” remarked producer Gilbert Gates,

“the louder your voice is heard.”

Now, thanks to producers and directors like Stephen Gaghan,

Charles Roven and George Clooney, I was fortunate to have my voice

heard in a very, very positive way on two feature films—“Three

Kings” and “Syriana.”

The men and women that I worked with on those two features were

absolutely terrific.

They, I would say, embraced 90 percent of the suggestions that I

offered to eliminate stereotypes.

But my main goal was to help them make a better movie without

offending anyone. So

they deserve a tremendous amount of credit—but, again, my presence

on the set made a tremendous difference.

I say that because when I initially read the screenplays, I

thought they were the worst—I can’t use the word.

Anyway, they were bad.

All right, four years ago, there were some signs of encouragement.

Four years ago, members from New York University came to our

home on Hilton Head Island and took away 5,000 Arab artifacts, more

than 2,000 films and TV shows.

Now at NYU, there is the Shaheen Archive, which houses this

collection [APPLAUSE], which is available to scholars and students

and filmmakers worldwide.

What’s interesting about this collection is they put together

an exhibit called “A Is for Arab” (which is also the title of my new

book, which I will be signing at 6:00).

This “A Is for Arab” exhibit goes all around the country to

universities, and it’s available just to cover the cost of postage.

My wife, bless her heart, it was her idea to create the Shaheen

Scholarships, and each and every year, we award scholarships to

young Arab-American students majoring in media.

To date, we’ve awarded over 70 media scholarships to

encourage these young people to become involved. [APPLAUSE]

Young Arab and American Muslims—I was doing research, I had to do

research for this, because this was something fresh, and I told

Delinda I wouldn’t use any of my old notes.

I found young Arab American filmmakers and Muslim

Americans—comedians like Maz Jobrani, Ahmed Ahmed, Dean Obeidallah,

all three of them—not only do they do standup acts, but they produce

movies, feature films.

Jobrani did four—“Jimmy Vestvood: Amerikan Hero,” “Brown and Friendly.”

Ahmed Ahmed did a great film called “Just Like Us.”

Dean Obeidallah did “The Muslims are Coming!”

They’re out there. I

discovered there are at least 10 Arab-American and Canadian women

who actively make feature films.

And there are at least two dozen women from the Arab world,

from 10 different countries, making feature films and documentaries.

Women like Saudi filmmaker Haifaa al-Mansour, who directed

the 2012 Academy Award-nominated drama

Wadjda.

We still have a long way to go, but these young women, along

with their male counterparts, are leading the way, replacing

damaging portraits with inventive, realistic images.

Fourth—I see the caution light is on—fourth, I’ll go quick.

Those [organizations] that do Arab film festivals throughout

the country are great.

They just do a marvelous job.

My only recommendation is that they bring in producers and

writers if they can, if their budgets allow—honor them, respect

them, and showcase them during their festivals.

Finally, the fifth and final suggestion: major organizations such as

the ADC—of which I’ve been a charter member since, well, I won’t say

when but I’ve been a major member for a long time.

Anyway, they should become active and acknowledge more often

image makers whose films enhance tolerance and image makers who

vilify Arabs. They

should do this on a regular basis.

They should let the trade papers know so it gets inked.

Use social media such as Twitter and Facebook.

We need to let them know that

we know what they’re doing, and acknowledge those who are doing

things to shatter myths.

Stereotypes don’t exist in a vacuum.

They injure people, especially children.

Damaging myths also injure those who may look Arab—black,

Sikhs, Native Americans, Hispanics and others.

They give ammunition to recruiters for extremist groups like

the Islamic State, ISIS.

They use these stereotypes to recruit members in their propaganda

films. History teaches

us the more people and their faiths are vilified, the more they are

“them” and not “us.”

There have been scores of TV series over the years focusing on

physicians and lawyers and broadcasters and journalists.

Yet to my knowledge, not one of these series ever featured an

Arab-American protagonist in medicine.

We have never seen the equivalent of a pioneering heart

surgeon, Dr. Michael DeBakey, or Dr. George Hatem.

George Hatem, there’s a statue of him in China because of the

wonderful work that he did there.

We have never seen the equivalent in law of a woman like

Rosemary Barkett, the [former] chief justice on the Florida Supreme

Court, or someone like our friend Ralph Nader.

In journalism, we’ve never seen the equivalent of Arab

Americans like Leila Fadel, National Public Radio’s bureau chief in

Cairo and a Shaheen scholarship recipient.

Or Michael Sallah, the

Miami Herald’s

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist.

From the beginning, I have always proposed that image makers project

Arab and Muslim characters as three-dimensional humane

individuals—no better, no worse than they project other people.

Why don’t they include in future scenarios a doctor, like

“Dr. Victor Nassar, At Your Service”?

A lawyer like Michael Rafeedie and a reporter like George

Hishmeh? Why not?

Are we not part of America’s landscape?

Have we not made great contributions in these fields and

others? Then we should

be part of the visual landscapes on television and in cinema.

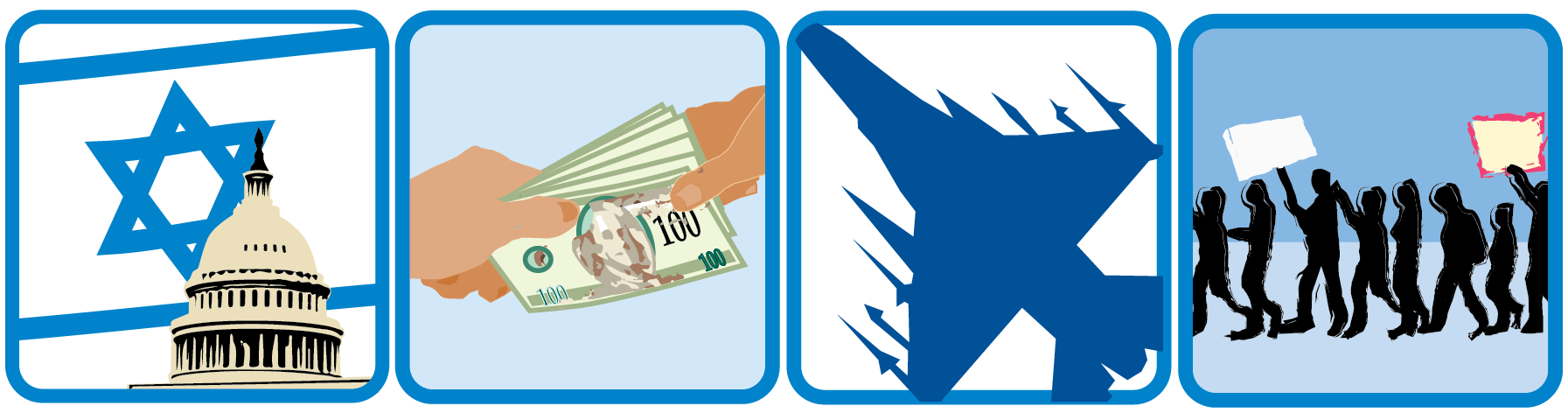

In conclusion, perceptions impact public opinion and public

policies. I’ll repeat

it. They impact opinion

and public policies.

Given the rise of ISIS and recent terrorist attacks here and abroad,

shattering stereotypes is more difficult today than ever before.

Politicians and members of some special interest groups

actively campaign to vilify all things Arabs and Muslims.

Resulting in what?

More hate crimes, more harassment, more fear, more deaths,

notably innocent Arabs and Muslim Americans, college students in

North Carolina, a Christian Lebanese in Tulsa, an imam in Queens, as

well as the deaths of anyone who is perceived to be Arab or

Muslim—an Indian in Kansas, a Sikh in Washington.

Unfortunately, there are those who do not see or care about the

difference between Sikhs and sheikhs.

Media images continue to teach us whom we should love and

whom we should hate. Yet

in spite of the current barrage of hate rhetoric and racist policies

and damaging images, I remain an optimist.

I have faith in young scholars and image makers, because I

always believe the future belongs to them and to the men and women

in the industry who are humanists.

Let me just give you two examples of two shows that I just saw.

One is a CBS sitcom called “Superior Donuts.”

In this one episode, there’s a dry cleaning shop owned by

Fawz, an Iraqi American.

Someone sprays on Fawz’s windows, “Arabs go home.”

When Arthur, who runs Superior Donuts, the donut shop, sees

that—Arthur is Jewish, by the way—he takes a rag and he removes that

from Fawz’s window. Then

he takes a can of spray paint and sprays on his window of the donut

shop, “Arabs welcome.”

Arabs welcome—that’s a telling moment, I think, in TV sitcoms.

There are other shows, but in the interest of time, I’ll skip

them.

Finally, there’s Mandy Patinkin, who stars in the series “Homeland.”

He admitted for the first five seasons, Muslims were the bad

guys. Admitting that

because it’s an on-the-edge-of-your-seat political drama, the series

was not helping the American Muslim community.

“We take responsibility for it. We are part of the problem,”

he said. “But we also

desperately want to be part of the cure.”

And then Richard Gere speaking out against the way

Palestinians were being treated in the occupied territories.

To rebuke these peddlers of prejudice—you like that: peddlers of

prejudice? I think I

stole it from someone. I

don’t remember who, but I like it.

To rebuke these peddlers of prejudice, I think that we should

keep in mind two things.

First, the wisdom of Václav Havel, former president of the Czech

Republic, who reminds us that none of us as an individual can save

the world as a whole, but each of us must behave as though it was in

his or her power to do so.

Finally, yesterday I went to the African American Museum, whose

moving displays reflect the damage that hateful stereotypes did for

centuries upon the African American people of our country.

I thought when I was there of one quote from Dr. Martin

Luther King, Jr. King

was in a jail in Birmingham, Alabama, and he said something like, “I

think the people who have ill will have used their time more

effectively than have the people of good will.”

He says, to change all of this, we should become movers and

shakers.